How Behavioural Science Can Help You Survive the Holidays

Christmas is, for many, ‘the most wonderful time of the year’ and whether you celebrate it or not, there are a breadth of activities and experiences, feelings and frustrations unique to the holiday season. However, while our environments may be filled with tinsel and trees, our decision making, and behavioural pitfalls remain squarely rooted in our unconscious – and many may even be exacerbated. With an especially high degree of emotionality (affect) during the holiday season, and undue pressures and stressors, our mental states are subject to changes too…for better or worse1. To keep ourselves sane, and decrease the burden on our cognitive capacity, mental shortcuts (or heuristics) may be working overtime along with Santa’s elves, making us particularly prone to bias.

So, in the spirit of the season, with only a week to go to Christmas, today our three Behavioural “Ghosts of Christmas” are delivering their lessons (albeit in reverse order); highlighting some behavioural holiday pitfalls to watch out for, and some hacks to get you through the season, or perhaps the whole year through.

The Behavioural Ghost of Christmas Future – Forecasting Failures

Generally speaking, humans are poor forecasters, and overly optimistic about the success of their plans2. This inability to properly predict has been attributed to overconfidence3, and causes us to fail to plan, or hold too-narrow a view to accommodate the unexpected variations during the holidays. So, if you’ve ever felt like you’re perpetually behind schedule during the holidays, and that nothing’s going quite to plan, you’re not alone. Planning fallacy3 explains an underestimation of just how long a given (holiday) to-do might take – whether it’s travel time on icy roads, parking at the mall, or getting the turkey in the oven early enough. We tend to believe it will be a shorter endeavour to put up Christmas lights, ignoring the past years’ excruciating labours of bulb replacement . When people are asked when they expect to be done with their Christmas shopping, they underestimate time spent in stores, online or the shipping time on an online gift purchase.

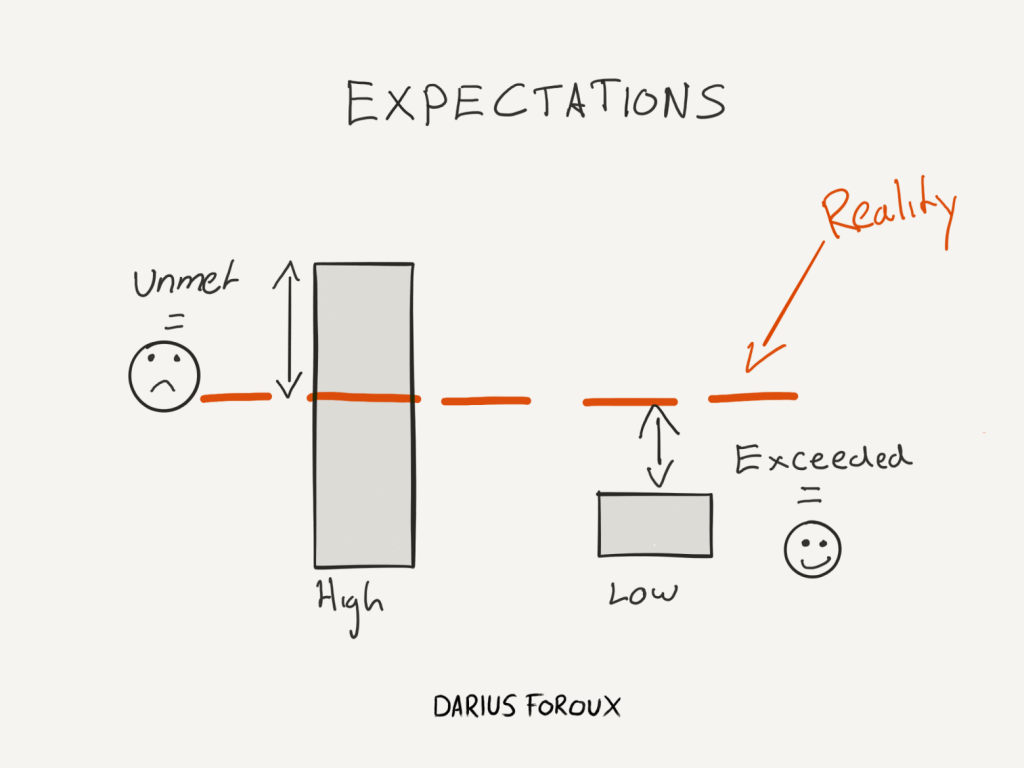

Our feelings may be unpredictable as well, as we tend to overestimate emotional valence (an inherent ‘goodness’ or ‘badness’) or intensity level4. Our emotional affect is also tied to our hedonic adaptation – the adaptability or ‘return to normal’ of our mood, and gradual decay of our experienced happiness over time when the novelty of change wears off; shiny new toys don’t stay engaging for very long5.

One hack for the planning fallacy is to put more detail in your plan. Rather than generally planning to “Christmas shop”, you’d likely be more successful by including specific shops along the way, note the distance from each, and give yourself a bit of ‘overconfidence buffer’ for parking time and line-up time. Research also suggests that when we are estimating timelines on behalf of others we are more accurate in our predictions. So try imagining a friend or family member having to make it through your to-do list, or simply ask someone else how long they estimate it will take you.

The Behavioural Ghost of Christmas Present(s) – Gifts, Ads and BS

At their core, our spending habits are intrinsically tied to our failure to delay gratification. A classic manifestation of this is the [in]ability to properly consider the future value of money, a propensity known as hyperbolic discounting. In essence, we drastically devalue rewards the further out in time they are, to the point where immediate consumption takes precedent6.

In the context of the holidays this may show up in a few non-monetary ways: those extra helpings of Christmas cookies or sweet potato casserole (which we at Salient fully support!), leading to a (future) stomach ache and tighter trousers come January, or a brilliant wine pairing, followed by another, and another, followed by a big headache on Boxing day. In behavioural economics, one of the most classic examples of the impacts of hyperbolic discounting, however, is shown in our spending behaviours.

Modern Christmas traditions, and the typical overspending and overconsumption involved, have come under a lot of recent criticism, citing marketing ploys for wasted money and trashed gifts no one needed or asked for. Generosity may well feed into this: we are often buying for others, rather than ourselves, and studies have shown that spending money on others does promote our own happiness7. Given this, it’s no wonder that we may fall victim to overspending as opposed to considering our savings when buying Christmas gifts. While this may be something we can get on board with once a year – so long as it doesn’t put our financial stability in jeopardy when the visa bill regret rolls around in January-, we are fighting a myriad of behavioural battles when we are out at the shops (or at home shopping online) around the holidays.

“The John Lewis Effect” has long been recognized as an ‘affective’ and ‘effective’ tool for marketing products by using the power of emotional stories in advertising campaigns to increase spending behaviour. Behavioural science studies have shown just how impactful emotions are in the context of decision-making, particularly in the context of consumer choice8; indeed, marketing departments have known this, and made good use of the insight since the dawn of commercialism. To remain top of mind when shoppers come to choose a product, companies evoke strong emotions through their adverts to drive purchases – and it works! Emotion-based advertisements for goods from home appliances, to computers, to spas have all shown higher uptake when compared to those which are information-driven9.

Christmas commercials, pulling at our heartstrings, put us in an elevated state which reduces our ability to resist unnecessary spending and makes brands more memorable – a key in driving spending behaviour. It also strongly grounds a brand identity at the most lucrative time of year for consumer goods sales, which may trigger unnecessary or unsustainable levels of gift-buying.

To make your spending more salient, try using cash! This simple swap – the physical use of money – may have a strong impact on slowing our outlays…and only watch those John Lewis ads once your holiday gift shopping is all done.

The Behavioural Ghost of Christmas Past – Making Memories

Emotional affect is also a critical element in the creation of memories. As it turns out, in many cases we will fondly remember the highlights of a vacation10 which confirms our pre-existing beliefs that we ought to enjoy our holidays (thus decreasing cognitive dissonance and making us feel nice and warm inside). We may happily forget an argument with our mother-in-law or the chaotic preparation and amount of work required to serve our relatives Christmas dinner. Instead, our minds look back and remember fondly the nieces/nephews or grandkids opening their presents, wide-eyed and jubilant, or the cozy fire while watching It’s a Wonderful Life on Christmas eve.

This disproportionate remembering is especially pronounced when an experience finishes on a positive note. Rarely do we remember the ‘average’ of an entire experience – our memories are typically formed around the highest ‘pleasure points’ as well as the very end of an experience. This is called the ‘peak end effect’11. Conversely, it’s possible that one extraordinary disaster can spoil an otherwise lovely season (to best avoid those, see above for planning fallacy!).

Luckily, this means the whole of the holiday doesn’t have to live up to perfection. The behavioural hack here is all rooted in our ability to reflect on our internal attitudes and expectations. The meal doesn’t have to be incredibly elaborate (indeed, studies have shown that our skills in differentiating between more expensive selections from the frugal are dismal) and that ambience arguably makes much more of a difference when people are evaluating quality12…besides, if you’re 3 bottles of wine in, who really notices anymore?

Take what you need and leave the rest.

Perhaps the greatest lesson I’ve learned from Christmasses past, is that letting go of the hyper-elevated expectations of any holiday greatly decreases the potential for disappointment. Not every bulb needs to be lit, not every stocking needs to be overflowing, and if the sink starts leaking on Christmas baking day, that’s okay too. Actively choose to highlight and participate in the bits that bring you the most joy and leave the rest. Insofar as possible, go with the flow…and remember, as long as something nice happens right at the end (Hallmark movies have this formula nailed), that’s the bit you will remember!

Wishing you a very sparkly season of warmth and wonder…Merry Christmas!

Salient designs and implements interventions to biases as well as explores the relationships between behavioural science research and industry practice. Get in touch with us to learn more.

References

- Hughes, B. (2018, December 6). What is the psychological impact of Christmas? https://jrnl.ie/4375551

- Sharot, T. (2011). The optimism bias. Current Biology, 21(23), R941-R945.

- Khaneman, D., Lovallo, D., & Sibony, O. (2011, June). Before You Make That Big Decision. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from www.hbr.org

- Wilson, T. D., Gilbert, D. T. (2003). Affective Forecasting. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 35, 345-411

- Frederick, S., & Loewenstein, G. (1999). Hedonic adaptation. In D. Kahneman, E. Diener, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology (pp. 302-329). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Laibson, D. (1997). Golden eggs and hyperbolic discounting. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112, 443-477.

- Dunn, E.W., Aknin, L.B., Norton, M.I. (2008). Spending Money on Others Promotes Happiness. Science, 319(5870), 1687-1688. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1150952

- Timson, E., (2017, December 20). The John Lewis Effect and what small businesses can learn from it. Small Business Co.Retrieved from https://smallbusiness.co.uk/what-is-the-john-lewis-effect-and-why-does-it-work-2542008/

- Ul-Abideen, Z., Saleem, S. (2011). Effective advertising and its influence on consumer buying behavior. European Journal of Business and Management, 3(3), 55-65.

- Kahneman, D. (2000b). Evaluation by moments: Past and future. In D. Kahneman & A. Tversky (Eds.), Choices, values, and frames (pp. 693–708). New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Russell, J. A. , & Pratt, G. (1980). A description of the affective quality attributed to environments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 38(2), 311-322.