Tale as old as time…as the end of January approaches, many well-intended New Year’s resolutions have inevitably failed to thrive or have been put on hold until the next fresh start (Monday?). If this sounds like you, you’re certainly not alone: according to studies, while 40% of Americans set New Year’s resolutions, a mere 10% of those follow through1. By analysing over 30 million January activities, Strava, an online social network for athletes, has even dubbed the second Friday of January “Quitter’s Day”2 – the date that most people are likely to give up on their fitness resolutions.

It seems to be notoriously difficult to translate a goal made at New Year’s into actual behaviour change, yet we begin January 1st with a killer combination of bright, shiny motivation and heavy-hitting willpower to achieve the goals we’ve set ourselves.

Given that resolutions are often in our own best interests, and things we ourselves believe we want to do, why can’t we make it stick?

Timing is a large factor. Arguably, the first week or two of our new behaviour – be it exercising more, quitting smoking or getting enough sleep – often take place during the tail-end of the holiday season. We are often on holidays, perhaps more relaxed, and most of us are out of routine, with more time to commit to our goals. As the new year progresses, however, we get busy: back to work and to our many commitments. The competing activities take up our time and energy, making it easy to fall back to our default, familiar behaviours and struggle to exercise the willpower necessary to stick with our resolutions. Indeed, habit formation takes a significant amount of time (an average of 66 days3) and unfortunately, consistency during those first few days of the year is generally not enough to form a longer lasting habit.

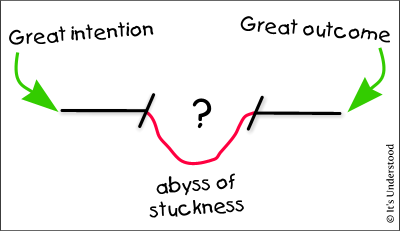

Mind the Gap

While timing may, in part, explain the ‘failure to resolve’, what’s helpful to understand is another reason we lack follow through. It has to do with varying degrees of each individual’s Intention-Behaviour Gap, the sometimes vast and insurmountable chasm between our resolve to act (or not act) and the reality of how we actually perform4. This is due in part to the relative ease with which we set goals, but the missing link to begin striving towards them. Our intentions are for future behaviour, often months or years down the line, but our actual behaviour happens in the here and now. These are extremely difficult to align, as we are inherently less able to reconcile these temporal selves, and to do what’s good for a future version of ourselves we don’t readily relate to.

So, you didn’t fail your New Year’s resolution, your New Year’s resolution failed you.

Fortunately, there are ways in which behavioural science can help us bridge the intention-behaviour gap and increase our chances of withstanding the necessary period of habit formation.

Commit intelligently

People tend to use New Years and other temporal landmark dates for goal setting but assigning New Year’s as the ‘right’ time to start a resolution is perhaps its biggest downfall. We see similar effects throughout the year, with something called the Monday Effect, or the inclination to start over with our goals on Mondays. Unfortunately, these fresh starts may not be the best way to begin goal striving. Choosing Monday, or January 1st as an arbitrary reset day can backfire substantially, because when we inevitably stumble it leads us into a cycle of “I’ve failed and so I need to start again; I might as well wait until next Monday/month/New Year’s.” Instead, committing when a goal is important, at a time that has ‘personal relevance to you’ is more likely to facilitate success in your habit formation5.

Once we’ve set a goal, research shows that a very powerful way to overcome our present bias and stick to it is by using commitment devices. These are mechanisms which ‘lock’ us into an intended plan or restricts our choices in the future. If your resolution was to get out and exercise more, signing up for a 5km race (and paying the fee to do so, see sunk cost fallacy, is likely to improve your chances of hitting the pavement. Bonus: making a public commitment is a double whammy for follow-through – tell your network about it. Nike and other apps connected to physical activity trackers automatically post times and distances for runners online, which may increase motivation, and success in goal striving6.

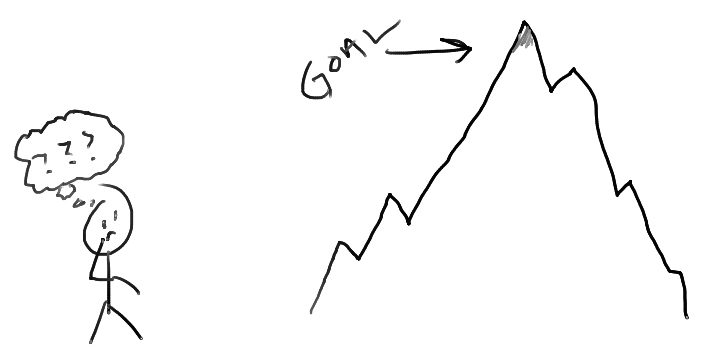

Break it down

Dividing your goals into digestible, small steps (think, tiny, seemingly ridiculously small, but completely accomplishable increments of progress) helps increase our intrinsic motivation through the feeling of accomplishment as we make progress towards our (larger) goal. These small steps also bring our ‘future’ self closer to our ‘current’ self, giving us a more tangible target (rather than an infinite horizon of tomorrows, out of reach and difficult to visualize). More concrete goals are also associated with closer temporal proximity, making commitments easier to stick to.

Lofty goals are still attainable, of course, so aim at the highest goal you can manage, but incremental movements towards the goal (those which might be difficult, which will stretch and challenge you) should be taken in turn to be the most promising for success. Clinical data and practice in cognitive behavioural therapy suggests that by identifying a larger behaviour change and breaking it down into smaller and smaller pieces until it’s small enough that someone will voluntarily confront it, bolsters confidence and the ability to take subsequent steps forming a sustainable, repeatable behaviour, or habit. It is of far less importance what the action is, simply that a first step is taken – just enough to start. As these actions are taken and we put ourselves in new situations, new neural connections are formed and the ‘pathways’ supporting our intended behaviours deepen (think about exercise, and muscles responding to a new ‘load’ or situational stress; they adapt) and things get easier7.

Phone a friend

Research also shows that a reliable way to boost your chances of sticking to a resolution or developing a new habit is to make the activity social8. Enlisting the help or camaraderie of an accountability buddy, provides several benefits: 1) it may make the endeavour more fun (or, if it’s tedious, misery loves company), 2) there is a default source of encouragement and motivation when your resolve is weary, and, perhaps most importantly 3) a feeling of responsibility leads to consistency, so as to not let your partner down. (Be mindful of the group size for this type of commitment device, however: at a certain size of group, this individual responsibility to show up will get watered down very quickly.)

Social accountability, like taking part in a team can be motivating, and incite socially normative behaviour and perhaps even some fun competition to play to our egos. But even if no one wants to get on board with the same particular goal you have, simply sharing goals with a friend creates commitment and bolsters follow-through. A study by Dr. Gail Matthews found that by sending weekly updates to a friend reporting their progress, 70% of participants were successful in achieving their goals, compared to 35% who were not9. As humans, we want to align ourselves with our stated public persona and verbalised commitments. It allows us to maintain a consistent view of self, and that makes us feel good.

Give it a rest

An overlooked, but critical element impacting our ability to make change is sleep. “Why We Sleep” by Matthew Walker, made it to the top of our reading list in 2019. In his book, Walker lists the numerous benefits of getting sufficient sleep every night and the harmful effects of neglecting good sleep habits (poorer decision-making, memory, physical and mental wellbeing)10. The majority of us rarely get the optimal amount of sleep to function at our best, and it might come as no surprise that a lack of sleep has an adverse effect on our ability to exercise willpower 11. If we aren’t well-rested, we aren’t doing ourselves any favours when trying to enact change and pursue goals. Indeed, it could be that resolving to take better care in our sleep habits could lead to success in other behaviour change in 2020 and beyond.

Of course, not everything runs according to plan in the path to goal attainment, whether you set out at New Year’s or not. The weight of disappointment in ‘falling off the wagon’ directly leads to the ‘fresh start/Monday effect’ if we adopt an all-or-nothing mentality with our resolutions. This ends up delaying progress towards our goals, as waiting to start again next week (or next year!) eats up time in which we could be making a lot of progress (rather than immediately brushing ourselves off and taking a small step in the right direction). It’s okay to slip up, change path, or adjust goals as we move our way towards them, and the time and energy spent on negative self-reflection has a detrimental effect on our subjective wellbeing, and ultimately our engagement and motivation.

Overall, evidence suggests that perhaps the best way to stick to your New Year’s Resolution, is not to make one. Instead, be mindful of what type of change you’re trying to achieve, how best to set yourself up for success, and establish a timeline that is meaningful to you. Set a goal, tell a friend, have a nap, do one tiny thing at a time, and be patient as you watch yourself succeed.

References

1. “New Years Resolution Statistics – Statistic Brain”. statisticbrain.com. 9 January 2018. Retrieved 19 April 2018.

2. Barr, S. (2018, January 12). Quitters’ Day: People Most Likely To Give Up New Year’s Resolutions Today. Independent. Retrieved from http://independent.co.uk

3. Lally et al. (2010). How are habits formed: Modelling habit formation in the real world. European Journal of Social Psychology. 40. 998-1009. 10.1002/ejsp.674

4. Meijin, C. (2019) Endurance Performance in Sport. Taylor and Francis

5. Dai, Hengchen & Milkman, Katherine & Riis, Jason. (2014). The Fresh Start Effect: Temporal Landmarks Motivate Aspirational Behavior. Management Science. 60. 2563-2582. 10.1287/mnsc.2014.1901.

6. Graef, S. (2017, April 6). Sharing Your Fitness Goals On Social Can Hold You Accountable. Huffpost. Retrieved from http://huffpost.com

7. Peterson, J. (Guest). (2018, November 29). “#1208 – Jordan Peterson.” The Joe Rogan Experience [Audio podcast]. Retrieved from https://podcasts.apple.com/ca/podcast/the-joe-rogan-experience/id360084272?i=1000424846374.

8. Milkman & Duckworth. (2018) Using Behavioral Science to Build an Exercise Habit. Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/using-behavioral-science-to-build-an-exercise-habit/

9. Gardner & Albee. (2015) Study focuses on strategies for achieving goals, resolutions. https://www.dominican.edu/dominicannews/study-highlights-strategies-for-achieving-goals

10. Walker, M. (2017). Why We Sleep. Scribner

11. Pilcher, J. J., Morris, D. M., Donnelly, J., & Feigl, H. B. (2015). Interactions between sleep habits and self-control. Frontiers in human neuroscience, 9, 284. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2015.00284